The keys to my heart

Wednesday, June 10, 2015

Eight-minute read

I learned to type on a manual typewriter.

By college, computers and word processors had taken over, but in grade school and high school it was still click click click ding.

Getting the letters to swing the 8- or -10 inch arc and strike the paper with a solid thwack took some force. A typist on one of these machines had to hit through the key and do a clean followthrough.

The IBM Selectric that came after was much easier to use. I recall it hummed menacingly when switched on. The keys felt more like switchgear – hard plastic, mechanical and stiff. Hitting one unleashed momentary fury.

Bang.

The keys, the vibration, the keystrikes were all tactile, a true mechanical device, not at all like the computers we use today.

In college, I traded up again. The student paper where I worked had a bank of computers with IBM PS2 keyboards. For many, this was legendary, the Stradivarius of keyboards. It was a solid, heavy slab embedded with key switches that made a firm, clean click when pressed.

Apple’s Extended Keyboard II is fondly remembered by longtime Mac users for many of the same reasons. They felt mechanical, like the typewriters that they replaced. Only better.

At this point I’m at risk of sounding like I’m about to tell about how I tied an onion to my belt, “which was the style at the time.” But this isn’t a nostalgia trip about historical keyboards so much as a riff on Henry Ford’s “people would have asked for a faster horse” line.1

Trading up isn’t always obvious. Or, more specifically, what you are trading up for often isn’t.

All those machines were heavy, big and moderately unpleasant to use by today’s standards. Typing fast on most non-electric typewriters was a practiced skill. The keyboards on those machines – really any machine – says something about them.

They’re antiques now, but in their day they were technology. They were the result of someone setting out to make the best object they could using available materials, budgets, manufacturing constraints and design goals.

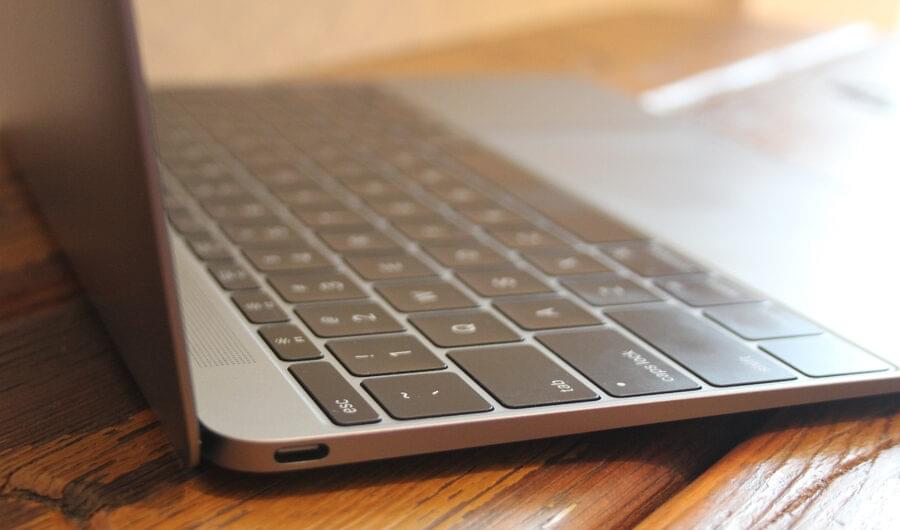

This is another way of saying my favorite mantra: Design is about choices. I have a good example of that right in front of me. I’m writing this review on the new 12-inch Retina Macbook.

The computer is extremely thin and light, impossibly so. A mere wisp. My formerly light and portable 13-inch Retina MacBook now feels like I’m walking around with a paving stone in my bag. This new laptop is so thin and light that it makes a 13-inch MacBook Air look like a Ford F-150 SuperCab parked next to a Mini Cooper.

To accomplish this Apple made sharp design compromises. The keyboard is barely there. This has proven to be one of the more controversial design decisions that Apple has made recently.

It feels significantly different to type on than current Mac keyboards. It’s not the same as typing on glass, but the keys are not fully buttons, either. Thanks to a new mechanism the keypress feels precise, more precise than regular MacBooks, actually. But there’s much less key travel.

For some, this is just a step too far. Another Apple folly. The notorious hockey puck mouse on the original iMac. The beautiful but overpriced G4 Cube 2.

Here’s Marco Arment, creator of Instapaper and the grumpy “hey, you kids, get off of my lawn” one-third of the Accidental Tech Podcast, on his experience with the 12-inch MacBook:

I can type on the MacBook, but I’d rather not. What I hadn’t considered was that even though I had common tasks that could fit within the MacBook’s limited specs – email, writing, chat – all of them required a lot of typing. Oops.

For this and other reasons – too slow, the trackpad – he hate-quit his MacBook and returned it. “Hate” isn’t an exaggeration. “I just hate using it,” he says in summary. I probably would have gone with “it’s a good machine, but it’s not for me,” but it’s his blog and he can say what he wants.

His critique is onto something, though. The keyboard is the key to understanding what the machine is about. If you hate the keyboard, you’re going to hate if for all the other compromises that went into it.

The machine is best understood as an intentionally limited device.

For some people, like me, this 12-inch will be a replacement for a larger MacBook. But Apple is positioning this machine against super-portable devices, such as the Microsoft Surface or its own iPad.

And it completely blows away Microsoft’s keyboard covers or typing on glass. Or iPad keyboard attachments.

People who choose the new MacBook will get the advantages of a super-light, thin, fanless laptop with all-day battery life and a better keyboard than all other devices in its class.

It took a couple days, but I realized how the keyboard was supposed to work. Your fingers glide over the keys that respond to a much lighter lighter touch. I feel like I’m beating the keys on my regular MacBooks now. A week in I’m finding that I’m not only used to the keyboard but that I actually like typing on it.

It’s different enough that it takes adjustment. Think of someone used to a manual typewriter being confronted with a modern MacBook keyboard.

For some, this sounds like The Simpsons Mrs. Krabapple telling students who were complaining about their uncomfortable new chairs that “eventually your bones will change shape.”

But I’ve been pondering the idea of technology changes, about how keyboards have evolved through the years to suit needs, ever since the machine came out and complaints started. But, I suspect there’s more than just pursuit of thinness going on here.

Apple has a tendency to adopt ideas that are counter to what has been done for years, decades even. But when you think about why Apple did it, the idea actually makes more sense.

Case in point: Natural scrolling. Scrolling down on a trackpad to make content go up on the screen is a vestige of scroll bars, c.1984. It’s a layer of abstraction added because of the limitations of technology at the time.

Natural scroll, by comparison, is direct manipulation of onscreen content – just grabbing stuff and moving it around. It’s like the real world. It’s the interaction model touchscreen devices use.

My buddy and I debate which scrolling method is correct. (Answer: Natural scrolling. Period.) But down-to-go-up scroll is understandable only as tradition, not something cognitive or intuitive.

This machine feels like Apple making a forward-looking decision in this vein. Future laptops will only get lighter and thinner, more like mobile devices. And the standard for mobile devices is typing on glass.

Is this a step toward Apple going all the way and just ditching mechanical keyboards someday? Maybe. Apple has clearly been headed that direction with its trackpads for some time.

The new lineup of MacBooks replace physical trackpad clicks with haptic feedback and multitouch. Right now a user can select, double click, move things, etc – everything a clicky trackpad can do – without ever actually clicking the trackpad.

Clicking is a vestige of the past, a time when a mechanical button was the best available technology to send input to the computer. Considering available technology, clickless trackpads actually make more sense. Users interact just fine with mobile devices with no physical button clicks for app input.

The haptic feedback trackpad on the 12-inch MacBook is really just Henry Ford’s faster horse. It behaves they way it does because of expectations, not needs. But this progression is still a sign Apple is headed somewhere else.

This keyboard – this laptop – is a statement. 3 It’s an opinionated design. It’s future-looking.

I think of my young nephews. They do most of their typing on an iPad. That’s their frame of reference. A minimalist keyboard would be an improvement to them. For this generation, expectations are going to be quite different.

And down the road is where Apple is always looking.

- This quote it probably apocryphal, but it makes a nice point.

- I own a G4 Cube. It is an amazing machine visually and design wise, especially the computer guts that lift out like a nuclear core. The machine is in the MOMA permanent collection. It serves the same role at my place, sitting on a shelf looking beautiful.

- It’s also a sign. If Apple likes anything, it’s cost savings from economies of scale. Expect this thin keyboard to show up across the line as their machines undergo redesigns.